An Explainable Reinforcement Learning Approach for Enabling Robots to Coach Humans

Best Technical Paper Runner-up @ Human-Robot Interaction conference 2019

Team members:

Aaquib Tabrez

Shivendra Agrawal

Bradley Hayes (Advisor)

Paper

2019

While much of the existing robotics literature focuses on making robots better at performing tasks, this work explores how we can use that proficiency and expertise to allow robots to provide personalized feedback with the goal of coaching humans to improve task performance. We investigate the challenges faced by robots while coaching humans (e.g., providing corrective feedback) during collaboration and how explainable AI can be leveraged to alleviate these challenges for fostering trust, teamwork, transparency.

Robotic Coaching in HRI:

In a collaborative task involving mixed human-robot teams, coaching helps to correct or improve the behavior of human collaborators by leveraging a robot teammate’s capabilities. Correcting or repairing the behavior of a teammate is even more important in critical applications where missteps could lead to financial losses, catastrophic failures, or risks of physical harm.

In general, coaches engage in a range of communication skills including providing feedback, insights, and clarifications to help learners shift their perspectives about the task and thereby discover alternate and better ways to achieve their goals.

Here, we focus on two key innovations from our work that contribute toward enabling proficient autonomous coaches:

- Reward Augmentation and Repair through Explanation (RARE): A novel coaching framework for understanding and correcting an agent’s decision-making process

- Human subjects study results showing that justification is an important, potentially necessary factor for convincing people to accept an agent’s advice.

Reward Augmentation and Repair through Explanation (RARE):

Operating under the assumption that humans behave rationally to maximize reward when performing a task, our core insight is that suboptimal behavior can be framed as an indicator of a malformed reward function being used by an otherwise rational actor. Under this model, providing corrections to the actor’s reward function will allow them to “reconverge their policy” to perform more optimally.

The process of Reward Augmentation and Repair through Explanation can be characterized through three interrelated challenges:

- Inferring the most likely reason for suboptimal behavior, by determining which parts of their reward function are malformed.

- Determining a policy trade-off between task execution and intervention, and

- Providing the necessary feedback and/or guidance to improve their performance.

To make #1 tractable, we apply this work within a domain with sparse reward function (R(s) is only non-zero for a subset of states) and operate under the assumption that malformed reward functions occur only because the actor is missing information as opposed to using incorrect information (e.g., given actor reward function R and true reward function R, R(s) = 0 for some values of s where R(s) != 0. We do not address the more general problem of cases where R(s) = x and R*(s) = y for x != 0).

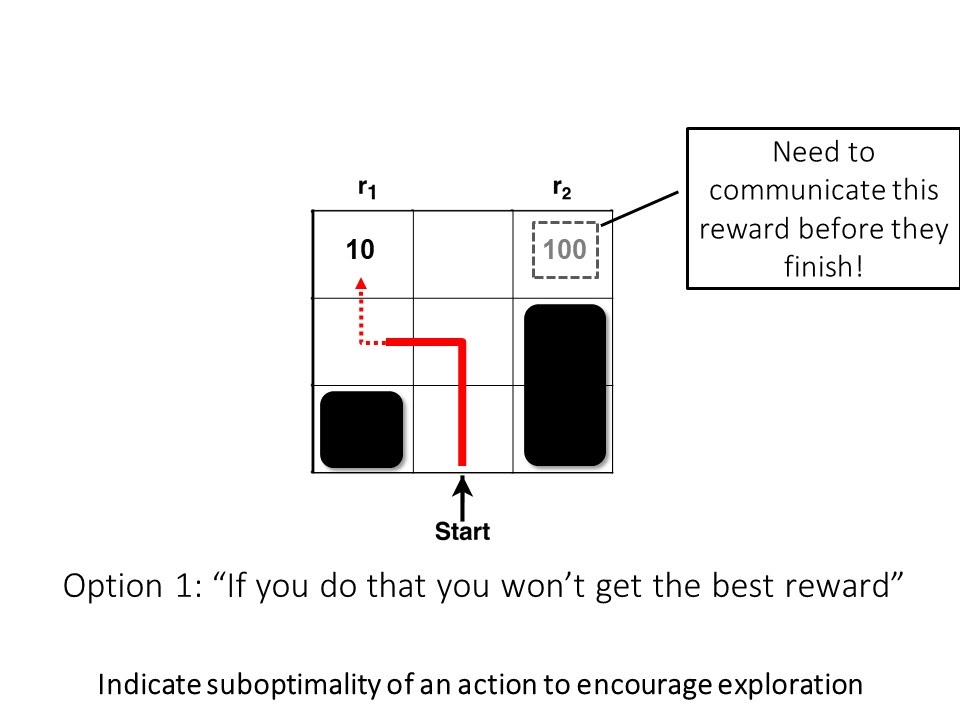

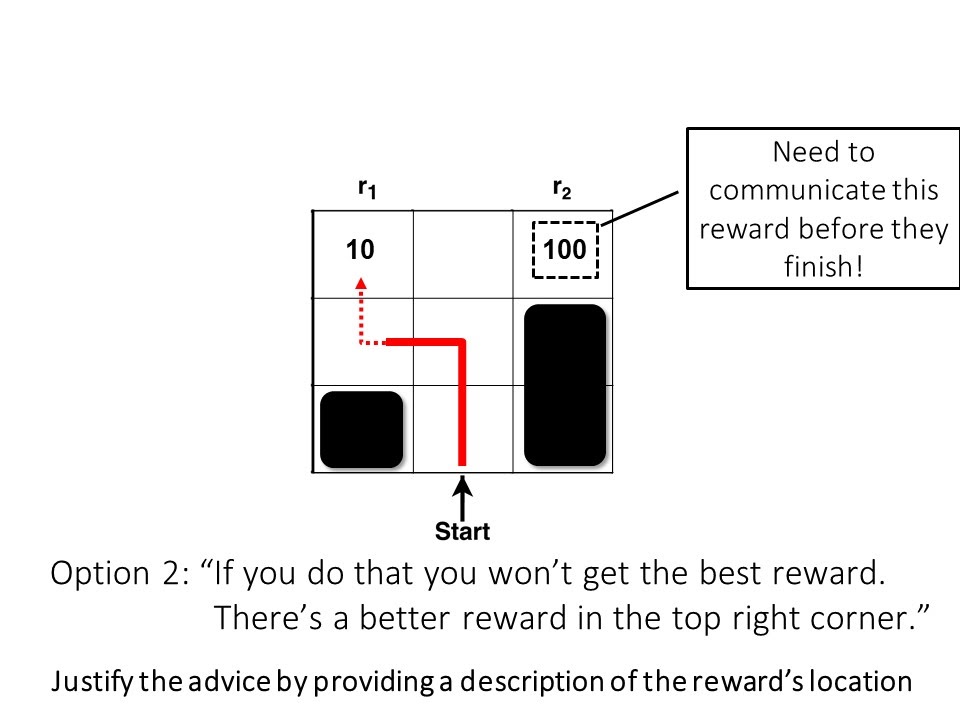

Here, we explain the intuition behind RARE through an example. Consider a grid world below (Figure 1) with two terminal states having rewards of 10 and 100. Given a knowledgeable, rational individual we would expect to see them collect the bigger reward. However, if we see a person going after the sub-optimal reward (10), then the only way to preserve the rationality assumption is to assume that they must not know about the bigger reward — in other words, that their world model is incomplete/inaccurate. Our robotic coaching technique involves what, how, and when we can tell the human collaborator about the inaccuracies in their task comprehension (reward function) such that they will have the option to improve their behavior (policy).

Figure 1: RARE framework estimating the missing reward factor (100) based on human behavior (red line)

Let’s look at the process of estimating the human collaborator’s mental model in the same example. In the first step, the robot observes the human at state S1 (Figure 2). Note that each state is composed of the world state and additional latent boolean variables that indicate the robot’s knowledge of the human’s awareness of each of the reward factors (r1, r2) in the world. At this stage, the robot doesn’t know if the human knows about either of the rewards. But at timestep 2, the robot can gather more information after observing the human’s next action. At timestep 2 the human is at state S2, and the robot still doesn’t know enough to take any action. But if the human goes to state S3 at timestep 3, the robot can infer that the human isn’t aware of the greater reward at the upper right corner. This answers the “what’’ (missing reward r2), but not the “when” or the “how”.

To address the “when”, we model the problem as a POMDP. In this case, we have a robot who is coaching while collaborating (i.e., the robot is able to participate in tasks as well as coach through explanation). Latent variables in the POMDP state space consist of Boolean variables indicating whether or not the human’s reward function contains each non-zero entry in R. While the robot’s understanding of the human’s mental model of reward is latent because we don’t actually know them beforehand and can’t observe them directly, we can gather clues to reduce state uncertainty by watching the human’s policy in action. By solving the POMDP, the robotic coach can successfully resolve when to take task-productive actions from the domain or communicative, reward repairing actions.

Figure 2: Procedural visualization of the estimation of human collaborator's mental model by the robot using RARE.

Finally, we are left with the challenge of resolving “how” the robot should convey the missing reward information to the human. While there are a number of choices, we investigate two classes of feedback: unjustified advice and advice with justification. An example of unjustified advice is to have the robot indicate the sub-optimality of the human’s action to encourage exploration (e.g., “If you do that you won’t get the best reward” or “That’s a bad move”). Advice with justification would entail having the robot provide a description of the reward’s location to supplement the advice (e.g., “If you do that won’t get the best reward. There’s a better reward in the top right corner.” or “If you do that you won’t get the best reward. There’s a large negative reward in region X.”).

Figure 3 Caption: RARE enables robotic coaches to repair sub-optimal policy by informing the human about the missing reward from their mental model.

Note: We use previous work from Hayes and Shah to describe state regions for natural language policy updates.

Figure 4: Options for providing reward coaching to improve the sub-optimal policy: 1) advice without justification and 2) advice with justification

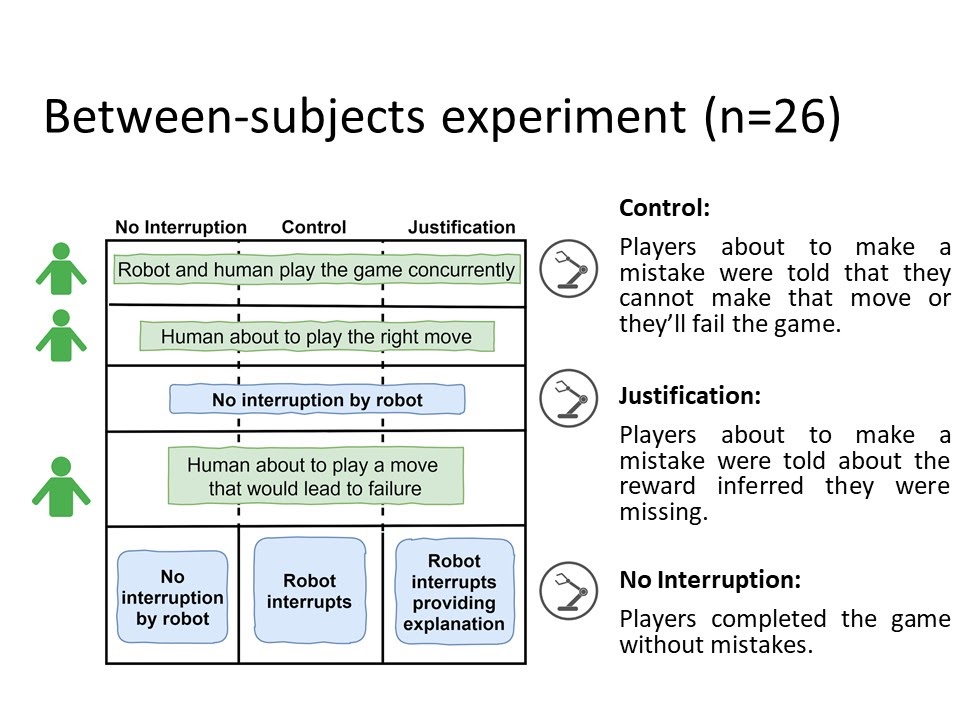

We performed a user study to test the strength of RARE and to figure out the best option to convey the missing reward.

Experimental evaluation and results:

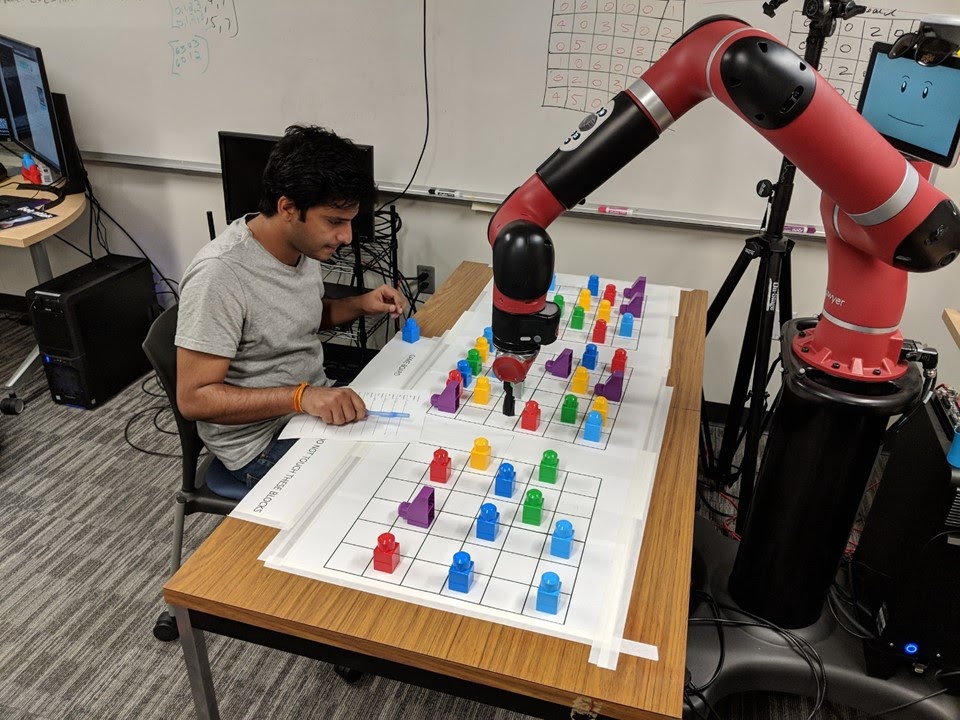

Figure 5 (Clockwise from top left)

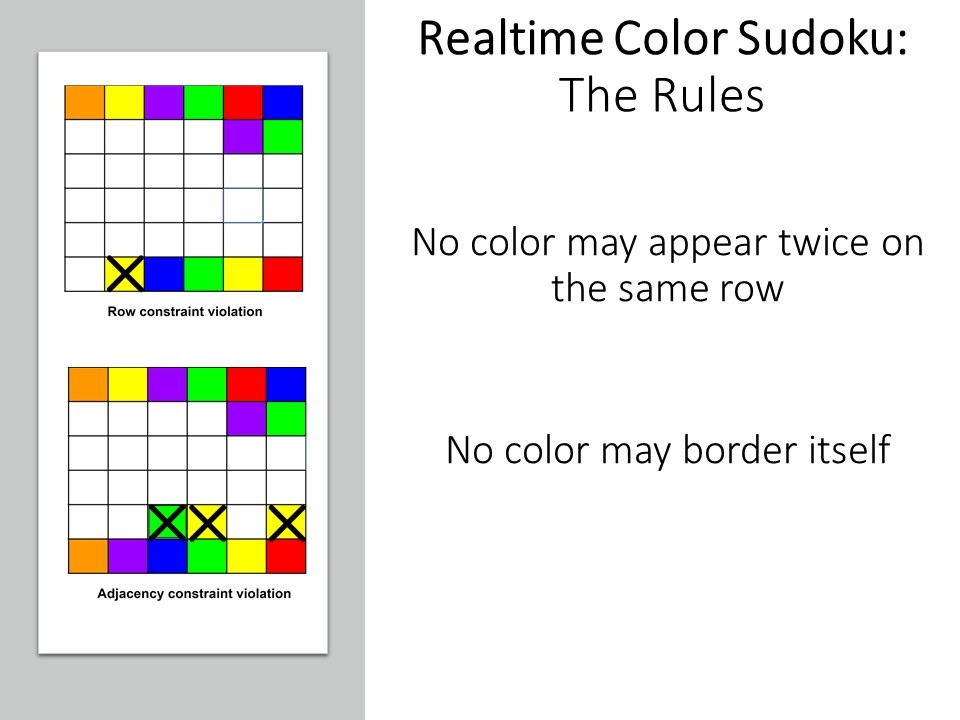

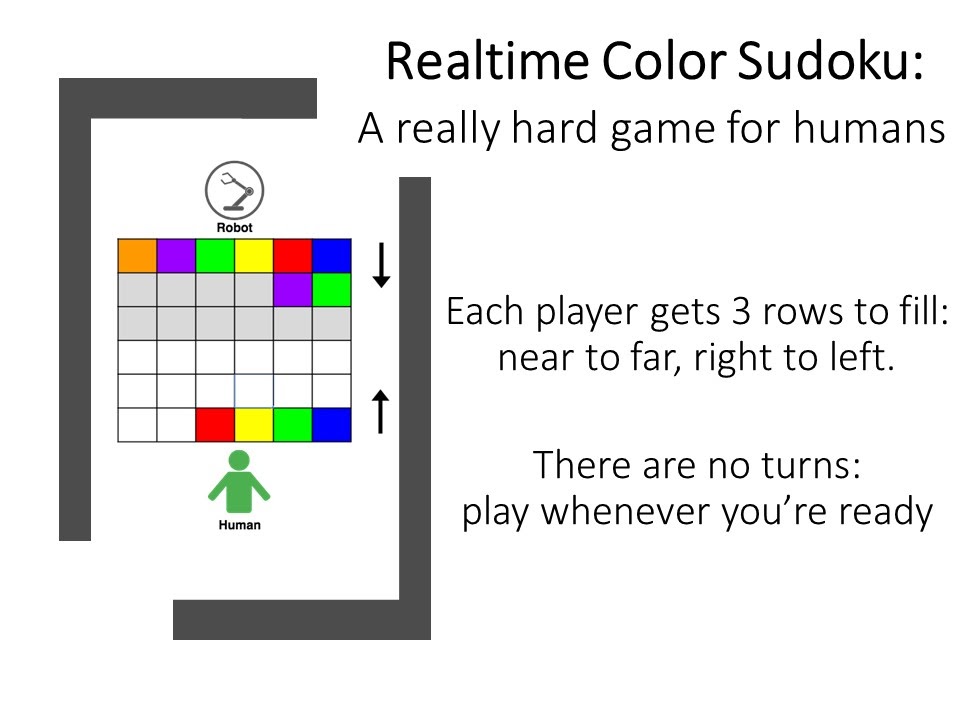

To determine the effectiveness of RARE and the usefulness of justification, we came up with a difficult game for people to play with a robot. We adapted the game of Sudoku and made it more challenging by putting it in a collaborative setting (see the above Figure 5 for details).

The subjective evaluation of our study shows that robots that provide justification for advice are perceived as more useful, helpful, and intelligent coaches compared to the control condition in which no explanation for failure was given. Another surprising result which emerged during the study was that people barely followed the robot’s advice (only 20% listened, while the other 80% of participants ignored advice and failed to solve the puzzle) when the robot did not provide any justification for its recommendation. In contrast, nearly everyone followed the robot’s advice (80% successfully completed the game) when justification was provided. Furthermore, we saw from open questionnaire responses that the participants had a more positive user experience in the justification condition.

Figure 6: Some of the participant feedback from the user study showing the contrast between the user experience in both condition

Conclusion:

To summarize, we developed a novel framework enabling an expert robot to coach a novice collaborator within a reinforcement learning context. We evaluated our framework in a challenging collaborative cognitive game with a human and a robot. We found that using justification during coaching makes robots more useful, helpful, and intelligent coaches.